PO Box 1611, Chico, ca. 95927

Web Site: http://buttecreekwatershed.org

The Butte Creek

Watershed Owner's Manual

What is a Best Management Practice?

Why should I care?

Best Management Practice is a term

used by many government agencies and resource professionals to describe the

best way of restoring, maintaining, or using the soil, water, plants and

animals on your property.

Our soil and the water that flows

over and through it are our most basic assets. The conditions of other natural

resources in a watershed, such as vegetation and animal life, are in many ways

indicative of the underlying health of watershed soil and water. The

inter-dependence of the many factors that make up natural resource systems

requires comprehensive planning and management. This achieves maximum long-term

benefits from natural resources, without diminishing their availability.

Planning and managing such a complex system cannot be done by single,

individual effort. It is best accomplished through the cumulative effects of

cooperative community awareness and involvement.

This Owner's

Manual was produced

with a generous grant to the Butte Creek Watershed Conservancy from the Great Valley Center through its LEGACI grant program. Each year, the

Center awards well over one-half million dollars in monetary grants to

non-profit groups, community organizations, and local governments that are

working to improve the well being of the Great Central Valley through

initiatives in the areas of Land Use, Economic development, Growth,

Agriculture, Conservation and Investment, (LEGACI).

The limitations of budget

and time required the scope of this Best Management Practices Manual to be

limited to land and homeowners with 40 acres or less. The subjects covered in

this Manual will be those encountered by our stakeholders controlling parcels

of 40 acres or less. This Manual is not intended to cover commercial

development or farming. Those subjects will be covered in a Best Management

Practice Manual for future publication.

The Owner's

Manual is designed to accomplish the goal of maintaining a sustainable

balance between the natural and human resources within the watershed. With increasing population and diversity of

land use in the watershed, a holistic approach to managing resources helps to

decrease negative impacts and to increase positive impacts. Economic vitality

is necessary to enable the community to address and solve resource problems

such as non-point source pollution, and maintaining a healthy natural resource

base is necessary for sustaining economic vitality.

Voluntary implementation of best management

practices not only helps deal with identified problems but prevents others from

occurring. The Owner's Manual is intended to serve as a preventive

maintenance effort, rather than the usual after the fact clean up or

mitigation program. Solutions to problems identified by citizens, landowners,

and agencies are more easily remedied when the problems are treated as vested

interests to be addressed, instead of positions to be defended. This proposal

provides the basis for a voluntary landowner effort to jointly address the

concerns expressed by the local community, while protecting and preserving the

natural and cultural resources in an economically reasonable manner. Preventive

care is the least burdensome and least expensive way to keep the watershed

healthy.

Preface & Acknowledgements

The Butte Creek Watershed

Owner's Manual

A Best Management Practice Manual

The

Butte Creek Watershed Owner's Manual is part of the Butte Creek Watershed

Conservancy's implementation of its Watershed Management Strategy. On November

14, 2000 the BCWC Board of Directors voted to accept the Watershed Management

Strategy. This Watershed Management Strategy is designed to accomplish the goal

of maintaining a sustainable river ecosystem for the Butte Creek watershed.

With increasing population and diversifying land use in the watershed,

coordinated management becomes beneficial. This decreases negative impacts and

increases positive impacts. Economic

vitality is necessary to enable the community to address and solve resource

problems. This maintains a healthy natural resource base, which is necessary

for sustaining that economic vitality. Establishment of a goal-oriented

management strategy can prevent problems before they occur, and will result in

less expensive and more efficient use of community energy and resources. This

important document can be viewed on the Conservancy's web site at: http://buttecreekwatershed.org.

Objective #2: in Chapter 1, Education and Public Outreach states: Develop a strong education and public outreach program to encourage conservation and wise use of natural resources and preservation of the economic and cultural heritage of the watershed.

Implementation 2.A states: Encourage development of a manual of Best Management Practices applicable to the continued multiple land uses found in the Butte Creek watershed and make this manual available to landowners and resource managers in the watershed.

We

thank the following people and agencies for their valuable assistance in the

production of the Butte Creek Watershed Owners Manual.

|

Kenneth N. Derucher, Ph.D. Dean and Professor California

State University, Chico |

John Icanberry US Fish and Wildlife

Service |

Paul Ward Biologist California

Dept. Fish and Game |

|

Glenn Nader Farm Advisor Livestock & Natural

Resources Sutter/Yuba/Butte

Counties |

Mike Madden Office of Emergency Services |

Great Valley Center Modesto, CA |

|

Laura Best Assistant

Editor |

Sharan Quigley Assistant Editor |

|

|

The Best Management Practices Committee: Rick Ponciano Rick Hall Sharan Quigley Morris Boeger Les Heringer Chuck Kutz Hank Evers Jack Bean Robb Cheal Ed Chombeau Ken Keller |

||

About the

Butte Creek Watershed Conservancy

The Conservancy received non-profit 501(c)3 status in November 1996. The Conservancy was created as a

landowner-driven group, and a 12-member Board of Directors directs its policies.

Current Board members are community leaders in agriculture, timber, cattle

grazing, local industry, and conservation. The Butte Creek Watershed Conservancy

was formed to encourage the preservation and proper management of the Butte

Creek Watershed through watershed-wide cooperation between landowners, water

users, recreational users, conservation groups, and local, state, and federal

agencies. The mission statement of the Conservancy reflects that dedication:

"The Butte Creek Watershed Conservancy was established to protect, restore, and

enhance the cultural, economic, and ecological heritage of the Butte Creek

Watershed through cooperative landowner action."

To join the Conservancy call (530) 893-5399 or Email us at:

creek@inreach.com

Write to:

Butte Creek Watershed Conservancy

P.O. Box 1611

Chico, CA

95927

|

Butte Creek originates on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada at an elevation of approximately 7,000 feet. Run-off originating from snow and rainfall feed six named and two unnamed tributaries that flow into the Jonesville Basin in Lassen National Forest in an area dominated by species of pine, cedar, and fir. Riffle substrate consists primarily of cobbles and gravel. In this reach, the stream flows all year, but peak flows generally occur between October and May. Early peak flows result from rainfall, and late season peak flows result from snowmelt. Stream temperatures remain cool all year and several species of trout are the dominant species of fish (Leach and Van Woert, 1968). Butte Creek cascades from the Butte Meadows area approximately 25 miles through a steep canyon to the point where it enters the valley floor near Chico. Numerous

small tributaries and springs enter the creek in the canyon area. Deep, shaded pools surrounded by species of

pine and fir form the landscape in the section of the canyon above Centerville, whereas the area below has a

shallower gradient and a riparian canopy of alder, oak, sycamore and willow. Several tributaries add flow to Butte Creek

in the canyon. Flows from the West Branch of the Feather River, diverted by Pacific

Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) for power generation, enter Butte Creek

via the Toadtown/Hendricks Canal at the DeSabla Powerhouse. PG&E and its predecessor (Butte County

Electric Power and Lighting Company) have utilized two dams to divert water

from Butte Creek for power generation since the turn of the century. Another diversion, the Forks of the Butte

Hydroelectric Project, was completed in 1991 by the Energy Growth Partnership

I. The lowermost structure, the

Centerville Diversion Dam, located immediately below the DeSabla Powerhouse,

is generally considered to be the upper limit of anadromous fish

migration. Spring-run chinook

salmon and steelhead trout utilize the canyon reach below the Quartz Bowl for

holding and spawning. |

Butte Creek enters the Sacramento Valley southeast of Chico and meanders in a southwesterly direction to the initial point of entry into the Sacramento River at Butte Slough. A second point of entry into the Sacramento River is through the Sutter Bypass and Sacramento Slough. Oaks, cottonwoods, and willows are common along the banks of the upper section of this reach (CDFG, 1974). The creek is bordered by levees in various areas of the valley reach. Four dams and numerous diversions in the valley section divert water from the creek for agricultural and wildlife purposes (McGill, 1987). Fall-run chinook salmon spawn predominantly in this reach between the Highway 99 crossing and the Western Canal crossing in October and November. Adult spring-run chinook salmon pass through this reach from March to June (CDFG, 1993). Juvenile salmon from both races rear here in late winter through late spring en route to the Pacific Ocean. Butte Creek water passes through the Butte Basin, Butte Sink, Butte Slough, and the Sutter Bypass before joining the Sacramento River. Creek water flows through twin channels, the East and West borrow pits, all year and Butte Slough Outfall during flood flows in the fall, winter, and spring. The borrow pits are regular, excavated channels on either side of the Sutter Bypass. The creek gains flow here through the return of irrigation water. Gates on Willow Slough and the East-West borrow pit diversion structure are used to control water levels in the East borrow pit (Slebodnick, 1976). Dams impound and divert water for wildlife and agricultural uses. Willows are the dominant riparian plant species. Butte Creek and Sacramento River salmon and steelhead rear in these waters throughout the year. The watershed's richly diverse and considerable natural resources provide ideal habitat for many aquatic and terrestrial species. The natural resources are also ideal for timber harvest, agriculture, and myriad recreational opportunities. Stewardship practices that consider all uses dependent on the watershed's natural resources will insure their continued preservation. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

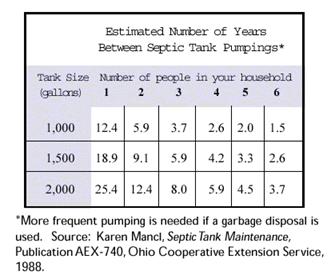

Onsite/septic system

owners need information on how septic systems work, how to maintain them, and

precautions to take to decrease the potential for the septic system to

contaminate groundwater or surface water. Operation and maintenance of the

system are the owner's responsibility. Managing a household

septic system requires that you control the volume and quality of wastewater

and maintain the septic tank and drainfield. A properly maintained system

should work correctly for many years. Volume of Wastewater

Sending wastewater to the tank too fast can cause

solid materials to pass into the drainfield without undergoing the gradual

anaerobic digestion that occurs in the septic tank.

Quality of

Wastewater

The quality of your wastewater, not just its

quantity, is also important in ensuring that your septic system functions

properly.

|

Maintaining

the Septic Tank

Slow accumulations of sludge and scum are normal.

You should remove these materials through periodic pumping and appropriate

disposal.

Maintaining

the Drain Field

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Maintaining Your

Septic System

Out of sight and

out of mind - does this describe your relationship with your septic system?

If you are like most homeowners, you probably never give much thought to what

happens to what goes down your drain. But if you rely on a septic system to

treat and dispose of your household wastewater, what you don't know can hurt

you. Proper operation and maintenance of your septic system can have a significant

impact on how well it works and how long it lasts, and in most communities,

septic system maintenance is the responsibility of the homeowner. Why Maintain Your

System?

There are three

main reasons why septic system maintenance is so important. The first reason

is money. Failing septic systems are expensive to repair or replace, and poor

maintenance is a common cause of early system failures. The minimal amount of

preventative maintenance that septic systems require costs very little in

comparison. For example, it typically costs from $3,000 to $10,000 to replace

a failing septic system with a new one, compared to approximately $50 to $150

to have a septic system inspected, and $150 to $250 to have it pumped. |

The second and

most important reason to maintain your system is to protect the health of

your family, your community, and the environment. When septic systems fail,

inadequately treated household wastewater is released into the environment.

Any contact with untreated human waste can pose significant health risks, and

untreated wastewater from failing septic systems can contaminate nearby

wells, groundwater, and drinking water sources. Chemicals

improperly released through a septic system also can pollute local water

sources and can contribute to system failures. For this reason it is

important for homeowners to educate themselves about what should and should

not be disposed of through a septic system. Finally, the

third reason to maintain your septic system is to protect the economic health

of your community. Failed septic systems can cause property values to

decline. Sometimes building permits cannot be issued or real estate sales can

be delayed for these properties until systems are repaired or replaced. Also,

failed septic systems can contribute to the pollution of local rivers, lakes,

and shorelines that your community uses for commercial or recreational |

|

|

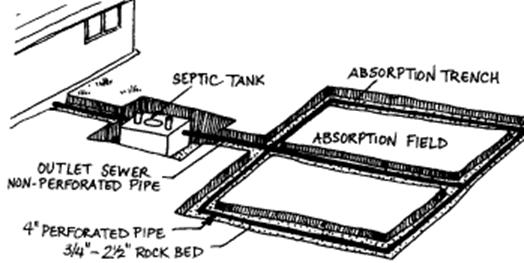

Typical Septic System Layout

Inspecting Your Septic System

Annual inspections

of your septic system are recommended to

ensure that it is working properly and to determine when the septic tank should be pumped. By inspecting and pumping your

system regularly, you can prevent the high cost of septic system failure. If

the sludge depth is equal to one third or more of the liquid depth, the tank

should be pumped.

A thorough

septic system inspection will include the following steps:

1. Locating the system Even a professional may have trouble locating your system if the access to your tank is buried. One way to start looking is to go in your basement and determine the direction the sewer pipe goes out through the wall. Then start probing the soil with a thin metal rod 10 to 15 feet from the foundation. Once your system is found, be sure to keep a map of it on hand to save time on future service visits.

2. Uncovering the manhole and inspection ports

This may entail some digging in your yard. If they are buried, try to

make inspections. Install risers (elevated access covers) if

necessary. 3. Flushing the toilets

This is done to determine

if the plumbing going to the system is working correctly. |

4. Measuring the scum and sludge layers

There are two frequently used methods for measuring the sludge and scum

layers inside your tank. The contractor may use a hollow clear plastic tube

that is pushed through the different layers to the bottom of the tank. When

brought back up, the tube retains a sample showing a cross section of the

inside of the tank. The layers can also be measured using long wooden sticks

or poles. As a general guideline, if the scum layer is within three inches of

the bottom of the inlet baffle, the tank should be pumped. If the sludge

depth is equal to one third or more of the liquid depth, the tank should be

pumped.

5. Checking the tank and the drain field

The contractor will check the condition of the baffles or tees, the walls of

the tank for cracks, and the drain field for any signs of failure. If your

system includes a distribution box, drop box, or pump, the contractor will

check these too. Properly sited, designed, constructed, and maintained septic systems can provide

an efficient and economical wastewater treatment alternative to public sewer

systems. While septic systems are designed and installed by licensed

professionals to meet the needs of individual sites, homeowners are

responsible for the system's operation and maintenance. |

Measuring

Sludge Accumulation

Sludge depth can

be measured by securing a towel around the bottom 3 feet of an 8-foot piece

of lumber. Lower the pole into the tank until it touches bottom and hold it

for several minutes.

BE CAREFUL! Never lean into or enter a septic tank. You could be

poisoned or asphyxiated. Never use matches or flames when inspecting a septic

tank. The gases generated in a septic tank are explosive and deadly.

Slowly raise the

pole and observe the towel. The discolored portion indicates the depth of the

sludge layer. Have the tank cleaned if it is more than 24 inches deep. A

septic plumbing contractor should be hired to pump out and inspect the tank.

If your tank has been recently installed, check the sludge and scum levels

every year to determine how rapidly solids are accumulating in the tank. |

Measuring Scum

Accumulation

The scum layer can be

measured by using a stick to which a weighted flap has been attached with a

hinge. When the flap-end of the stick is forced through the scum layer, the

weighted flap will fall into the horizontal position. Raise the stick until

resistance is felt from contact with the bottom of the scum layer. Place a

mark on the stick where it meets the top of the inspection port. Then

position the flap so that it is under the bottom of the sub-merged outlet.

Again, mark the stick where

it meets the top of the tank. Remove

the stick and note the distance between the two marks. Have the tank

cleaned if the distance is 3 inches or less. If you

choose to do these, remember that the liquid and solid contents of the septic

system are capable of causing infectious diseases. After working on any part of

the septic system, always wash hands thoroughly before eating, drinking, or

smoking. Change clothes before coming into contact with food or other people. |

Procedures for measuring the

accumulation of sludge

and scum

layers in a septic tank.

|

Water

Wells - Water Quality Testing |

|

|

Laboratory testing is the only sure means to detect

contaminants in your water. The following tests; nitrates, coliform bacteria,

pH, and total dissolved solids (TDS), if taken yearly, will give you a

general idea about the quality of your water. If these test results meet

federal and state standards, your water is probably of good quality. Call several different labs to find out their prices

and sampling procedures. The county extension office has a list of

state-certified labs and the contaminants they can analyze for. Some labs

will send you empty bottles with complete sampling instructions. Accurate

test results depend on how well you follow the directions. After the lab has completed the tests, they will send

you a copy of the results. Your local health department can probably help you

interpret the results.

Microorganisms

Microorganisms in your

drinking water can make you sick. Unfortunately, testing for all specific

types of harmful microorganisms is expensive and essentially impossible.

However, coliform bacteria are good indicators of the microbiological quality

of drinking water. |

Coliform

bacteria Coliform bacteria live in the soil, decaying plant

material, and the intestines of humans and animals. Microorganisms in your

water can cause various gastrointestinal illnesses such as dysentery and

cholera. The test for coliform bacteria is an indicator of the

microbiological quality of water. A positive coliform test means that your

water may be contaminated with other harmful microorganisms. A laboratory test for coliform bacteria is simple and

inexpensive. Call several certified labs for their costs and sampling

procedures. Be certain to follow the lab instructions carefully so you do not

accidentally contaminate the sample. If lab results show microorganisms in your water,

check the integrity of the well casing and grout seal around the borehole.

Water and contaminants can seep into the well from the surface if the casing

or grout seal is cracked.

You can decontaminate your well several ways. For

example, you can shock-chlorinate the system by putting large amounts of

household chlorine bleach directly in the well and allowing it to sit

undisturbed for up to 24 hours. To ensure purity, test the water one or two weeks

after shock-chlorinating. If your well is still contaminated, you must take

other measures. You may have to install a water-purifying unit at the well to

treat all the water entering your home. These units include continuous feed

pumps, ultraviolet lamps, and ozonation devices. Emergency

Disinfection |

|

Water

Wells - Pollution Causes |

|

|

California Water

Code Section 231 requires the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) to develop well standards to protect California's ground water quality.

The standards apply

to all water well drillers in California and the local agencies that enforce

them.

By law, DWR is responsible for issuing standards for constructing, altering, maintaining, and destroying wells to prevent pollution. DWR's well standards

provide minimum standards for the

construction, alteration, maintenance, or destruction of wells to prevent

pollution of ground water. |

Items addressed by DWR well standards include: • Setback of wells

from pollution sources • Casing materials • Annular seal

dimensions and materials • Surface features—pads, locks, covers,

backflow preventers, vaults • Well development • Disinfection • Repair • Destruction

Local governments,

counties, cities, and some water districts are responsible for enforcing

standards that are either equal to or more stringent than DWR's well

standards. These agencies usually require permits for well construction. They also conduct

inspections to make sure the wells are constructed properly. To determine who

enforces well standards in your community, contact your local county environmental

health department. |

|

In 1994, the California Building Standards

Commission approved guidelines for installing "graywater" systems

in homes throughout the state. The move was a significant step in making

reuse of some residential wastewater a reality. "Graywater" refers to water already used

in the washing machine, bathtub or shower. Subsurface plumbing systems

allowed under the standards allow homeowners to reuse such water for

irrigating trees, landscaping, and other ground cover. The standards include

a number of provisions aimed at educating homeowners and ensuring safe use of

graywater. Systems generally consist of a three-way diverter

valve, a treatment assembly such as a sand filter, a holding tank, a bilge

pump, and an irrigation or leaching system. The holding tank cools the water

and temporarily holds it back from the drain hose. Systems can either be custom designed and

built, or purchased as a package. Techniques include recessed or raised

planter soilboxes, water injection without erosion, gravity or pressure leach

chamber, and irrigated greenhouses. Some system components can retrofit

existing irrigation systems. Because conventional wastewater plumbing lines combine black and graywater, separating the two generally involves a parallel wastewater system. Space must be available for larger components such as a holding tank or some filters, which can be located in a basement, shed, or possibly outside. |

Benefits/CostsBeside the initial cost of separating black and

greywater plumbing lines, and sand filter costs about $1000, plus one or more

hours of labor. Prices are site-specific and vary widely depending on flow

rate, water quality, temperature, and the local building authorities. In new

construction, the septic wastewater treatment system can often be downsized

as a result of reducing its expected load, and separation of the plumbing

lines will be simpler and less costly than in a retrofit installation. LimitationsContaminants such as paint, bleach, and dye must

be diverted to a separate treatment process such as a septic tank. Periodic maintenance of the graywater

treatment system is required. Code/RegulatoryLocal regulations, sanitary engineers, inspectors,

and boards of health might not be familiar with or permit these methods.

Graywater separation might also not be justification for downsizing the

septic system. AvailabilityThere are several local distributors of tank and

filtration systems; pumps are widely available. Other system components are

essentially conventional construction materials. |

|

Rain Water Harvesting System Components |

||

|

|

||

|

Whether the system you are planning is large or

small, all rainwater harvesting systems comprise six basic components: 1.

Catchment Area/Roof, the surface upon which

the rain falls, 2.

Gutters and Downspouts, the transport channels

from catchment surface to storage; 3.

Leaf Screens and

Roofwashers, the systems that remove contaminants and debris; 4.

Cisterns or Storage Tanks,

where

collected rainwater is stored; 5.

Conveying, the delivery system for

the treated rainwater, either by gravity or pump; and, 6.

Water Treatment, filters and equipment, and

additives to settle, filter, and disinfect. |

||

1. CATCHMENT AREA

The catchment area is the surface on which the

rain that will be collected falls. Channeled gullies along driveways or swales in yards can also serve as

catchment areas, collecting and then directing the rain to a French drain or

bermed detention area. Rainwater

harvested from catchment surfaces along the ground, because of the increased

risk of contamination, should only be used for lawn watering. For in-home use, the roofs of buildings are

the primary catchment areas, which, in rural settings, can include

outbuildings such as barns and sheds. A

"rainbarn" is a term describing an open-sided shed designed with a

large roof area for catchment, with the cisterns placed inside along with

other farm implements. |

|

|

|

Rain Water Harvesting System Components |

|

|

2. GUTTERS AND DOWNSPOUTS These are the components that catch the rain from

the roof catchment surface and transport it to the cistern. Standard shapes and sizes are easily

obtained and maintained, although custom-fabricated profiles are also

available to maximize the total amount of harvested rainfall. Gutters and downspouts must be properly

sized, sloped, and installed in order to maximize the quantity of harvested

rain. |

Gutter

Filter

Downspout

Filter

|

3. ROOFWASHERS

Roof washing, or the collection and disposal of

the first flush of water from a roof, is of particular concern if the

collected rainwater is to be used for human consumption, since the first

flush picks up most of the dirt, debris, and contaminants, such as bird

droppings, that have collected on the roof and in the gutters during dry

periods. |

|

4. STORAGE TANKS

Other than the roof, which is an assumed cost in

most building projects, the storage tank represents the largest investment in

a rainwater harvesting system. To

maximize the efficiency of your system, your building plan should reflect

decisions about optimal placement, capacity, and material selection for the

cistern.

|

Round

Cistern

|

|

Rain Water Harvesting System Components |

|

5. CONVEYING Remember,

water only flows downhill unless you pump it. The old adage that gravity flow

works only if the tank is higher than the kitchen sink accurately portrays

the physics at work. The water pressure for a gravity system depends on the

difference in elevation between the storage tank and the faucet. Water gains

one pound per square inch of pressure for every 2.31 feet of rise or lift. Many

plumbing fixtures and appliances require 20 psi for proper design

consideration. |

|

6. WATER TREATMENT Before making a decision about what type of water

treatment method to use, have your water tested by an approved laboratory and

determine whether your water will be used for potable or non-potable uses. Dirt, rust, scale, silt and other suspended

particles, bird and rodent feces, airborne bacteria and cysts will

inadvertently find their way into the cistern or storage tank even when

design features such as roof washers, screens, and tight-fitting lids are

properly installed. Water can be unsatisfactory without being unsafe;

therefore, filtration and some form of disinfection are the minimum

recommended treatment if the water is to be used for human consumption

(drinking, brushing teeth, or cooking). The types of treatment units most

commonly used by rainwater systems are filters that remove sediment, in

concert with either an ultraviolet light or chemical disinfection. FILTERS

Filtration can be as simple as using cartridge

filters, or those for swimming pools and hot tubs. In all cases, proper

filter operation and maintenance in accordance with the instruction manual

for that specific filter must be followed to ensure safety. Once screens and

roofwashers remove large debris, other filters are available which help

improve rainwater quality. Keep in mind that most filters on the market are

designed to treat municipal water or well water.

Rain Water Filter |

Composting ToiletsComposting toilets can close the nutrient cycle, turning a dangerous waste product into safe compost, without the smell, hassle, or fly problems. They are usually less expensive than conventional septic systems and they will reduce household water consumption by at least 25%.

Basic System A composting toilet has three basic elements: a place to sit, a composting chamber, and a drying tray. Most models combine all three elements in a single enclosure, although some models have separate seating, with the composting chamber installed in the basement or under the house. In either case, the drying tray is positioned under the composting chamber, and some sort of removable finishing drawer is supplied to carry off the finished product. |

Ninety percent of what goes into a composting toilet is water. Compost piles need to be damp to work well, but most composting toilets suffer from too much water. Evaporation is the primary way a composting toilet gets rid of excess water. If evaporation can't keep up, then many units have an overflow that is plumbed to the household greywater or septic system. Warmth and air flow through the unit assist the evaporation process. Every composting toilet has a vertical vent pipe to carry off moisture. Air flows across the drying trays, around and through the pile, then up the vent to the outside of the building. The low-grade heat produced by composting is supposed to provide sufficient updraft to carry vapor up the vent. However, like any passive vent with minimal heat, these are subject to downdrafts. Electric composters use vent fans and a small heating element as standard equipment. There are optional vent fans for non-electric models that can be battery or solar-driven. Smaller composters certainly cost less, but because the pile is smaller they are more susceptible than larger models to all the problems that can plague any compost pile, such as liquid accumulation, insect infestations, low temperatures, and an unbalanced carbon/nitrogen ratio. Smaller composters require the user to take a more active role in the day-to-day maintenance of the unit. Smaller units with electric fans and thermostatically controlled heaters have far fewer problems than the totally non-electric units. So be aware that the less-expensive composting toilets have hidden, and long-range costs.

Smaller

System |

|

Soil Erosion

Soil, Erosion, and Sediment |

|

|

Soil is more than just the brown muddy stuff you track in after a rainstorm. It is an intricate composite of living microorganisms, organic matter, and mineral matter worn down from parent rocks. The process from rock to soil is a slow one. An average inch of topsoil, the richest of the soil layers in organic matter, takes hundreds of years to form. As any home gardener knows, soils vary widely in fertility, mineral content, physical structure and the way they react to wind or water. Some soils drain slowly, making them a poor surface for roads or septic systems. Others are highly erodible and at the least disturbance can lead to a gully or streambank washout. Soil erosion is a natural process. In stable watersheds the rate of erosion is slow, and natural healing processes can keep up with it. But in many watersheds, the high level of human disturbance has accelerated the rate of erosion beyond nature's healing qualities, and if not controlled, could have a long-term detrimental affect on Butte Creek. The effects of soil erosion are not limited to the site where the soil is lost. The detached soil, called sediment, enters the water system and settles out, at a culvert inlet, a stream channel, or in a lake. Some sediment is needed to bring nutrients and substrate materials to aquatic ecosystems, but too much sediment causes problems. In the water, sediments limit sunlight penetration, which robs aquatic plants of the light they require to live. In turn, fish and other aquatic animals are deprived of the oxygen provided by plants. Sand and silt particles moving through the water can literally scrub plants and animals off streambed surfaces. When waterborne soil particles eventually settle to the bottom of streams, they can smother fish eggs and other aquatic life. Sediments can also reduce stream channel capacity, causing further localized erosion and flooding. |

Plants are a natural, inexpensive, and highly effective means of controlling runoff and erosion. Runoff slows down when it reaches a strip of vegetation and lose much of its erosive force. Vegetation also works as a filter, straining out sediment and debris, and absorbing other pollutants. Some of the major problems caused by erosion are: Degradation of water qualityAs eroded material enters

streams and channels, it degrades water quality both in the streams and in

receiving waters such as Butte Creek. The eroded material contains nutrient

loading Flooding Development/Construction

|

|

Erosion Control Basics of Erosion Control |

|

Basic Rules for

Preventing Erosion

Protect bare soil surfaces. Vegetation is the best protection because it both absorbs and uses water. Minimize

hard surfaces to maximize the water absorption capacity of your

land. Avoid compacting soils by minimizing traffic and tillage operations

when soils are wet. Keep heavy equipment off exposed soil during the rainy

season. Use gravel for parking areas. Do not concentrate water flow unless absolutely necessary. On undisturbed slopes, water percolates through soil slowly and somewhat steadily. Even during heavy rainfall, runoff that can't be absorbed flows evenly over the ground surface into the nearest drainage. When all the runoff is focused on one spot, such as a culvert or a roof gutter, the natural protection of the ground surface is often not sufficient to prevent this extra flow from breaking through to bare soil.. If you must focus runoff, protect the outflow area with an energy dissipator, such as rock or securely anchored brush that will withstand stormflows. Limit livestock and human use of vulnerable areas. Livestock and people can provoke erosion by disturbing vegetation and creating trails that channel the flow. Disturb

existing vegetation as little as possible. The foliage and roots

or plants hold topsoil and even subsoil in place and regulate the speed of

water flowing through and over soil surface. The native plant community is

especially well adapted to suit specific soil and rainfall conditions. Once

it is disturbed by human activity, the soil becomes much more susceptible to

erosion. Of course we need to harvest resources and build homes; but if you

have a chance to leave native plants intact and keep them healthy, do! |

►Prepare erosion-control plan. ►Fence off sensitive areas. ►Minimize area of disturbance (including

access). ►Minimize duration of disturbance. ►Work during low-flow periods. ►Minimize use of heavy machinery. Use smallest

equipment possible. ►Do NOT clean equipment in a regulated area, or

where runoff will enter a drainage area. ►Do NOT dump or spill material into wetland. ►Remove excavated material in layers, and

replace in original sequence. ►Salvage native plant material. Consider

creating a wetland plant nursery on-site for later reintroduction efforts.

(This can be as simple as lining an area within a square of logs with

plastic, laying wetland plants in the lined cradle, and ensuring that they do

not dry out.) ►Return disturbed area to pre-construction

grade, and replant with appropriate native vegetation. ►Restore stream profile, substrate, and habitat. |

|

Erosion Control Structures Sheet Mulching & Outlet Protection |

|

SHEET

MULCHING

The installation of a protective covering (blanket) or

soil-stabilization mat. Plant fibers typically used for mulch include straw,

hay, and wood cellulose fiber.

DESIGN / IMPLEMENTATION

|

MAINTENANCE

OUTLET

PROTECTION

Erosion-resistant surface provided at the outlet of a water course. APPROPRIATE FOR:

DESIGN / CONSTRUCTION

MAINTENANCE

|

|

Erosion Control Structures Berms & Erosion Control Blankets |

|

BERMS

A ridge made of compacted soil.

to slow the flow of water in

order to increase infiltration into soil. DESIGN/CONSTRUCTION

MAINTENANCE:

|

EROSION

CONTROL BLANKETS

Material installed to

protect erosive soils on slopes, in drainages, and in high-use areas APPROPRIATE

FOR:

INSTALLATION

Follow manufacturer's recommendation regarding

stapling pattern. MAINTENANCE

|

|

An Aid to

Determine Present and Potential Road Erosion Problems Warnings found at road stream crossings (culverts and bridges):

Water

ponds upstream of culvert (CMP) inlet during storms.

Treatment: Inspect, clean and maintain CMP inlet;

install larger diameter CMP. Sediment

deposited from ponded water above culvert inlet.

Treatment: Clean inlet; install larger diameter CMP; upslope

instability problem inspection with expert. Woody debris deposited upstream of

culvert inlet. Treatment:

Frequent winter inspections; remove debris; install trash rack. Trash racks clogged above culverts

and/or in inboard ditches (IBD). Treatment:

Frequently inspect and remove debris from trash racks. High rust line in CMP (approximately

1/3 to 1/2 the height of the pipe may indicate an undersized pipe). Treatment:

Monitor in winter; replace with larger diameter CMP or bridge. CMP inlet or outlet is crushed or torn

and jagged bottom is worn through. Treatment:

Straighten inlet or outlet; replace pipe. Presence of diversion potential (water

will run down road when culvert plugs). Treatment:

Install rolling dip across road at, or adjacent to, culvert. Overflow

from a plugged culvert or inboard ditch has diverted down the road surface. Treatment: Clean out plugged culvert or

ditch; install rolling dip at, or adjacent to, the crossing; upgrade undersized

culvert. The gully

below the CMP outlet is larger than the gully above the crossing. Rills or gullies running down roadbed. Treatment:

Install rolling dips or waterbars, or outslope road. Saturated roadbed - rushes, sedges,

colts-foot, equisetum present. Treatment: Install French drain; cross road drain IBD if

cutbank is seeping saturated stream crossing may be caused by leaking,

clogged, or undersized CMP install new, larger CMP. Presence of tension cracks on road

surface. Treatment:

Expert consultation, excavate and/or construct full bench road. Rockfall on road, potentially due to

instability or cutbank or hillslope above. Treatment:

Inspect hillslope for failure potential, expert consultation. Warnings

found on inside edge of road: Warnings

found on outside edge of road: |

|

Erosion Control Structures Straw Bale & Sand Bag Barriers |

|

|

STRAW BALE BARRIERS Temporary structures to

guide runoff APPROPRIATE

FOR:

DESIGN

/ CONSTRUCTION

around the sides rather than

across top and bottom, to prevent deterioration of bindings.

|

MAINTENANCE:

(Flake and spread as mulch

over disturbed surfaces uphill from barrier.)

SANDBAG BARRIERS Temporary structures to guide runoff APPROPRIATE

FOR:

DESIGN/CONSTRUCTION: Height: 18" Base width: at least 48" Stack sandbags using an

alternately layered method. When waterproofing is

desired, cover with a plastic liner. Bury upslope/upstream end. MAINTENANCE:

|

|

Straw

Bale Barrier |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Straw

Catchment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Definition

A

grassed waterway/vegetated filter system is a natural or constructed

vegetated channel that is shaped and graded to carry surface water at a

nonerosive velocity to a stable outlet that spreads the flow of water before

it enters a vegetated filter. Purpose

Grassed waterways convey runoff from terraces,

diversions, or other water concentrations. Vegetation in the waterway

protects the soil from erosion caused by concentrated flows, while carrying

water downslope. The stable outlet is designed to slow and spread the flow of

water before the water enters a vegetated filter. Where used

The vegetated filter is

designed to trap sediment and increase infiltration so that other pollutants,

such as pesticides and nutrients, can be reduced from surface runoff. The

grassed waterway also offers diversity and cover for wildlife. Vegetation establishment

For the stable, spreading type outlet, select perennial plant species (native species are encouraged where possible) that has compatible characteristics to the site. Use sod-forming plants that have stiff, upright stems that provide a dense filter. Use the recommendations for filter strips for the area below the outlet. Establish vegetation before allowing water to flow in the waterway. Use irrigation and mulch to hasten establishment of vegetation as necessary |

Operation and maintenance

Wildlife

The grassed waterway and

filter system can also enhance the wildlife objectives depending on the

vegetative species used and management practiced. Consider using native or

adapted vegetative species that can provide food and cover for important

wildlife. Delay mowing of waterway and filter area until after the nesting

season. CONSIDERATIONS

Important wildlife

habitat, such as woody cover or wetlands, should be avoided or protected if

possible when siting the grassed waterway. If trees and shrubs are

incorporated, they should be retained or planted in the periphery of grassed

waterways so they do not interfere with hydraulic functions. Mid- or tall

bunch grasses and perennial forms may also be planted along waterway margins

to improve wildlife habitat. Waterways with these wildlife features are more

beneficial when connecting other habitat types; e.g., riparian areas, wooded

tracts and wetlands.

|

|

|

Grassed WaterWay |

|

|

|

Capacity

The minimum capacity

shall be that required to convey the peak runoff expected from a storm of

10-year frequency, 24-hour duration. When the waterway slope is less than 1

percent, out-of-bank flow may be permitted if such flow will not cause

excessive erosion. The minimum in such cases shall be the capacity required

to remove the water before crops are damaged. Velocity Design velocities shall not exceed those obtained by using the procedures, "n" values, and recommendations in the NRCS Engineering Field Handbook (EFH) Part 650, Chapter 7, or Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Agricultural Handbook 667, Stability Design of Grass-lined Open Channels. |

Depth The minimum depth of a waterway that receives water from terraces, diversions, or other tributary channels shall be that required to keep the design water surface elevation at, or below the design water surface elevation in the tributary channel, at their junction when both are flowing at design depth. Freeboard above the designed depth shall be provided when flow must be contained to prevent damage. Freeboard shall be provided above the designed depth when the vegetation has the maximum expected retardance. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Width

The bottom width of

trapezoidal waterways shall not exceed 100 feet unless multiple or divided

waterways or other means are provided to control meandering of low flows. Side slopes

Side slopes shall

not be steeper than a ratio of two horizontal to one vertical. They shall be designed to accommodate the

equipment anticipated to be used for maintenance and tillage/harvesting

equipment that will cross the waterway. |

Drainage

Designs for sites

having prolonged flows, a high water table, or seepage problems shall include

Subsurface Drains (NRCS Practice Code 606), Underground Outlets (NRCS

Practice Code 620), Stone Center Waterways or other suitable measures to

avoid saturated conditions. Outlets All grassed waterways shall have a stable outlet with adequate capacity to prevent ponding or flooding damages. The outlet can be another vegetated channel, an earthen ditch, a grade-stabilization structure, filter strip or other suitable outlet |

|

|

|

Conditions where practice applies

Where

access is needed from a private or public road or highway. Design criteria

Access

roads shall be designed to serve the enterprise or planned use with the

expected vehicular or equipment traffic. The type of vehicle or equipment,

speed, loads, climatic, and other conditions under which vehicles and

equipment are expected to operate need to be considered. Visual

resources and environmental values shall be considered in planning and

designing the road system. Access

roads range from seldom used trails to all-weather roads heavily used by the

public and built to very high standards. Some trails facilitate control of

forest fires are used for logging, serve as access to remote areas for

recreation, or are used for maintenance of facilities. Where

general public use is anticipated, roads should be designed to meet

applicable federal, state, or local criteria. Sound

engineering practices shall be followed to insure that the road meets the

requirements of its intended use and that maintenance requirements are in

line with operating budgets. Drainage Roadside ditches shall be

adequate to provide surface drainage for the roadway and deep enough, as

needed to serve as outlets for subsurface drainage. Channels shall be

designed to be on stable grades or protected with structures or linings for

stability. Water breaks or bars may

be used to control surface runoff on low-intensity use forest or similar

roads. SurfacingAccess roads shall be given a wearing course or

surface treatment if required by traffic needs, climate, erosion control, or

dust control. The type of treatment depends on local conditions, available

materials, and the existing road base. If these factors or the volume of

traffic is not a problem, no special treatment of the surface is required. Unsurfaced roads may require controlled access to

prevent damage or hazardous conditions during adverse climatic conditions. Toxic and acid-forming materials shall not be used

on roads. This should not be construed

to prohibit use of chemicals for dust control and snow and ice removal. Traffic safety Passing

lanes, turnouts, guardrails, signs, and other facilities as needed for safe

traffic flow shall be provided. Traffic safety shall be a prime factor in selecting the angle and

grade of the intersection with public highways. Preferably, the angles shall be not less

than 85 degrees. The public highway shall be entered either at the top of a

hill or far enough from the top or a curve to provide visibility and a safe

sight distance. The clear sight

distance to each side shall not be less than 300 feet, if site conditions

permit. Access Road Specifications

Construction

operations shall be carried out in such a manner that erosion and air and

water pollution are minimized and held within legal limits. The completed job

shall present a workmanlike finish. Construction shall be according to the

following requirements as specified

for the job: 1. Trees, stumps, roots, brush, weeds,

and other objectionable material shall be removed from the work area. |

Location Roads

shall be located to serve the purpose intended, to facilitate the control and

disposal of water, to control or reduce erosion, to make the best use of

topographic features, and to include scenic vistas where possible. The roads

should generally follow natural contours and slopes to minimize disturbance

of drainage patterns. Roads should be

located where they can be maintained and so water management problems are not

created. To reduce pollution, roads

should not be located too near watercourses. Alignment The minimum tread width is 10 ft for one-way traffic and 15 ft for two-way traffic. The tread width for two-way traffic shall be increased approximately 4 ft for trailer traffic. The minimum shoulder width is 2 ft on each side of the tread width. Where turnouts are used, road width shall be increased to a minimum of 20 ft for a distance of 30 ft. Side slopes

All cuts

and fills shall have side slopes designed to be stable for the particular

site conditions. Erosion control. If

soil and climatic conditions are favorable, roadbanks and disturbed areas

shall be vegetated as soon as possible and skid trails, landings, logging,

and similar roads shall be vegetated after harvesting or seasonal use is

completed. If the use of vegetation is precluded and protection against

erosion is needed, protection shall be provided by nonvegetative materials,

such as gravel or other mulches. Roadside

channels, cross drains, and drainage structure inlets and outlets shall be

designed to be stable without protection. If protection is needed, riprap or

other similar materials shall be used. General criteria

Filter

strips, sediment and water control basins, and other conservation practices

shall be used and maintained as needed. Dead

end roads shall be provided with a turnaround. In some areas turnarounds may

also be desirable for stream, lake, recreation, or other access purposes. Quality

1.

Short-term and construction-related effects of this practice on the quality

of on site downstream water courses. 2.

Effects on erosion and the movement of sediment, pathogens, and soluble and

sediment-attached substances that would be carried by runoff. 3.

Effects on the visual quality of water resources. 4. Effects on the movement of dissolved substances below the root zone toward the ground water. |

|

Preventing Washboarding |

|

|

One of the most aggravating gravel maintenance

problems that plagues motor grader operators, managers, and elected officials

is corrugation or "washboarding". It not only produces an uncomfortable

ride, but moderate to severe washboarding can cause a driver to have less

control of his or her vehicle. It actually becomes a safety problem. Main Causes of Washboarding

Lack of moistureWhen frequent rainfall occurs, washboarding is greatly reduced. Prolonged dry weather can cause washboarding in almost any situation, even with relatively low traffic. TrafficPoor quality gravelThere are several things to consider in determining quality. Washboarding will almost certainly develop it the surface gravel has poor gradation, little or no binding characteristic, and a low percentage of fractured stone. What is good gravel?

In prolonged dry weather, almost any section of road with a high traffic count will develop some corrugation, but good gravel will definitely reduce the problem. Good surface gravel should have a nice blend of stone, sand, and fines. Generally, the maximum size stone should be 3/4 inch. Crushed gravel that has a high percentage of fractured stone will have much better aggregate interlock and will stay in place on the road surface better than rock with a naturally rounded shape. This also gives the road better strength. There must also be a good mix of sand-size particles and fines. The ideal blend produces a gravel that will compact into a dense, tight mass with an almost impervious surface. This will reduce washboarding dramatically. |

Perhaps the least understood factor in obtaining good surface gravel is the right percentage and quality of fine material. This is the percentage of material that passes the #200 sieve. In order to resist washboarding, the gravel must have a good cohesiveness or binding characteristic. Commercial binders are available, but most people generally rely on natural clays. True clay, when it is separated down to individual particles, will be so fine that you cannot see the individual particles with the naked eye. These particles, when exposed to moisture, will cling together tightly, and this is what we want in our gravel. Obtaining good gravel in the field is the real challenge. Yet this is the place to begin fighting washboard problems. Start by establishing good specifications. We generally see close control of materials used in the base and the asphalt or concrete on our major constructions projects. However, when surface material is produced for the "plain old gravel road," very little attention is given to the specification. The real keys are to increase your knowledge of materials and then follow through by specifying what you want. Make this clear before you let bids for crushing and/or supplying gravel. Communicate with your supplier. Some pits or quarries do not have a good natural blend of material. In some cases, material such as clay or stone may have to be hauled in and blended at the plant. Don't

overemphasize a cheap initial cost for material. You will pay either way: by

purchasing cheaper material up front, spending more to maintain and replace

it over the years, and taking more complaints from the public, or by paying

more for quality material that requires less maintenance, lasts longer, and

generates fewer complaints. Remember also that trucking is often 70 percent or more of the total cost of gravel placed on the road. Spending more to increase the quality of the gravel itself does not change the total cost as much as you might think. |

|

ZONE |

Location |

Purpose |

Recommendation |

|

1 |

Begins

at the top of stream bank with a minimum width of 15 feet measured

horizontally on a line perpendicular to the streambank. |

Creates a stable ecosystem adjacent to the water's edge. Provides soil and water contact to facilitate nutrient buffering. Provides shade to moderate and stabilize water temperature and to contribute necessary detritus to the stream ecosystem. |

Dominant vegetation should be composed of a variety of native riparian tree and shrub species and such plantings as necessary for streambank stabilization. A mix of species will provide the prolonged stable leaf fall and variety of leaves necessary to meet the energy and pupation needs of aquatic insects. |

|

2 |

Begins

at the edge of zone 1 and extends a minimum average width of 20 feet measured

horizontally in the direction of flow. |

Provides

contact time for buffering process to occur and to sequester nutrients,

organic matter, pesticides, sediment, and other pollutants. |

Concentrated flow should be converted to sheet flow or subsurface flow before entering this zone. Predominant vegetation will be composed of riparian trees and shrubs suitable to the site, with emphasis on native species. |

|

3 |

Begins at the edge of zone 2 and extends horizontally in the direction of flow. |

Provides sediment filtering, nutrient uptake, and the space to convert concentrated flow to uniform flow. |

Vegetation

should be comprised of native grass and forbs. Zone 3 is only required for concentrated flow conditions dependent on

the site. |

|

Definition

Treatments

used to stabilize and protect banks of streams or constructed channels, and

shorelines of lakes, reservoirs, or estuaries.

Purpose

·

To prevent the loss of land or damage to land uses, or other

facilities adjacent to the banks, including the protection of known

historical, archeological, and traditional cultural properties. ·

To maintain the flow or storage capacity of the water body or to

reduce the offsite or downstream effects of sediment resulting from bank

erosion. ·

To improve or enhance the stream corridor for fish and wildlife

habitat, aesthetics, recreation. Conditions where practice applies

This

practice applies to streambanks of natural or constructed channels and

shorelines of lakes, reservoirs, or estuaries where they are susceptible to

erosion. It applies to controlling erosion where the problem can be solved

with relatively simple structural measures, vegetation, or upland erosion

control practices. General

Criteria Applicable to All Purposes

Measures

must be installed according to a site-specific plan and in accordance with

all applicable local, state, and federal laws and regulations. Protective

measures to be applied shall be compatible with improvements planned or being

carried out by others. Protective

measures shall be compatible with the bank or shoreline materials, water

chemistry, channel or lake hydraulics, and slope characteristics both above

and below the water line. End

sections shall be adequately bonded to existing measures, terminate in stable

areas, or be otherwise stabilized. Protective

measures shall be installed on stable slopes. Bank or shoreline materials and type of measure installed shall

determine maximum slopes. Designs

will provide for protection from upslope runoff. Additional

Improvement Criteria for Stream Corridor Stream corridor vegetative components shall be

established as necessary for ecosystem functioning and stability. The

appropriate composition of vegetative components is a key element in

preventing excess long-term channel migration in re-established stream

corridors. Measures shall be designed to achieve any habitat and population

objectives for fish and wildlife species or communities of concern as

determined by a site-specific assessment or management plan. Objectives are based on the survival and

reproductive needs of populations and communities, which include habitat

diversity, habitat linkages, daily and seasonal habitat ranges, limiting

factors and native plant communities. The type, amount, and distribution of vegetation shall be based on the

requirements of the fish and wildlife species or communities of concern to

the extent possible. Measures shall be designed to meet any aesthetic

objectives as determined by a site-specific assessment or management plan. Aesthetic objectives are based on human needs, including visual quality,

noise control, and microclimate control. Construction materials, grading

practices, and other site development elements shall be selected and designed

to be compatible with adjacent land uses. Measures shall be designed to achieve any

recreation objectives as determined by a site-specific assessment or

management plan. Recreation objectives

are based on type of human use and safety requirements. Considerations

An assessment of streambank or shoreline

protection needs should be made in sufficient detail to identify the causes

contributing to the instability (e.g. watershed alterations resulting in

significant modifications of discharge or sediment production). Due to the complexity of such an assessment

an interdisciplinary team should be utilized. When

designing protective measures, consider the changes that may occur in the

watershed. When appropriate, establish a buffer strip and/or

diversion at the top of the bank or shoreline protection zone to help

maintain and protect installed measures, improve their function, filter out

sediments, nutrients, and pollutants from runoff, and provide additional

wildlife habitat. |

Internal

drainage for bank seepage shall be provided when needed. Geotextiles or

properly designed filter bedding shall be used on structural measures where

there is the potential for migration of material from behind the measure. Measures

applied shall not adversely affect threatened and endangered species nor

species of special concern as defined by the appropriate state and federal

agencies. Measures

shall be designed for anticipated ice action and fluctuating water levels. All disturbed areas around protective measures

shall be protected from erosion.

Disturbed areas that are not to be cultivated shall be protected as

soon as practical after construction.

Vegetation shall be selected that is best suited for the soil/moisture

regime.

Additional CriteriaThe

channel grade shall be stable based on a field assessment before any

permanent type of bank protection can be considered feasible, unless the

protection can be constructed to a depth below the anticipated lowest depth

of streambed scour. A

protective toe shall be provided based on an evaluation of stream bed and

bank stability. Channel

clearing to remove stumps, fallen trees, debris, and bars shall only be done

when they are causing or could cause detrimental bank erosion or structural

failure. Habitat forming elements that provide cover, food, and pools, and

water turbulence shall be retained or replaced to the extent possible. Changes in channel alignment shall not be made unless the changes are based on an evaluation that includes an assessment of both upstream and downstream fluvial geomorphology. The current and future discharge-sediment regime shall be based on an assessment of the watershed above the proposed channel alignment. Measures

shall be functional for the design flow and sustainable for higher flow

conditions based on acceptable risk. Measures

shall be designed to avoid an increase in natural erosion downstream. Measures

planned shall not limit stream flow access to the floodplain. When

water surface elevations are a concern, the effects of protective measures

shall not increase flow levels above those that existed prior to

installation.

Consider conservation and stabilization of

archeological, historic, structural and traditional cultural properties when

applicable. Measures should be

designed to minimize safety hazards to boaters, swimmers, or people using the

shoreline or streambank. Protective measures should be self-sustaining or

require minimum maintenance Consider

utilizing debris removed from the channel or streambank into the treatment

design. Use construction materials, grading practices,

vegetation, and other site development elements that minimize visual impacts

and maintain or complement existing landscape uses such as pedestrian paths,

climate controls, buffers, etc. Avoid

excessive disturbance and compaction of the site during installation. Utilize

vegetative species that are native and/or compatible with local

ecosystems. Avoid introduced or exotic

species that could become nuisances. Consider species that have multiple

values such as those suited for biomass, nuts, fruit, browse, nesting,

aesthetics and tolerance to locally used herbicides. Avoid species that may

be alternate hosts to disease or undesirable pests. Species diversity should

be considered to avoid loss of function due to species-specific pests.

Species on noxious plant lists should not be used. Livestock

exclusion should be considered during establishment of vegetative measures

and appropriate grazing practices applied after establishment to maintain

plant community integrity. Wildlife may also need to be controlled during

establishment of vegetative measures. Temporary and local population control methods should be used with

caution and within state and local regulations. Measures that promote beneficial sediment

deposition and the filtering of sediment, sediment-attached, and dissolved

substances should be considered. Consider

maintaining or improving the habitat value for fish and wildlife, including

lowering or moderating water temperature, and improving water quality. Consideration

should be given to protecting side channel inlets and outlets from erosion. Toe

rock should be large enough to provide a stable base and graded to provide

aquatic habitat. |

|

|

Stream Crossing (Temporary) |

||

|

Stream

Crossings TEMPORARY APPROPRIATE FOR: Serving road and

trail detours while bridge and/or culverts are being constructed, repaired,

or replaced.

DESIGN/CONSTRUCTION:

|

NOTE: To minimize the adverse

impacts of on-site handling of fill imported or excavated for wetland

projects, protect wetland surfaces with geotextile or a 2' bed of straw

before depositing fill materials even temporarily. MAINTENANCE:

|

|

|

DESIGN

/CONSTRUCTION

preserve the integrity of

the root mat as much as possible.

|

|

Culvert and Drainage Ditches |

|

GENERALDESIGNCONSIDERATIONS:

dig them as deep as culverts

lie.

|

|

Why are Lake or Streambed Alteration Agreements

necessary? California's

lakes, rivers, and streams provide valuable habitat for fish

and wildlife. The Department of Fish and Game (DFG) is responsible for

conserving, protecting, and managing California's fish, wildlife,

and native plant resources. To meet this

responsibility, the Fish and Game Code requires notifying DFG of any proposed

project that may impact a river, stream, or lake. If DFG determines that

the project may adversely affect existing fish or wildlife resources, a Lake

or Streambed Alteration Agreement is required. By notifying DFG

and entering into a Lake or Streambed Alteration Agreement, you are

contributing to the protection and conservation of California’s natural

resources. Who needs to

notify the Department of Fish and Game? Notification to

DFG is required by any person, business, state or local government agency, or

public utility that proposes an activity that will:

What does DFG

consider Notification? The notification

requirement applies to any work undertaken in or near a river, stream, or

lake that flows at least intermittently through a bed or channel. This

includes ephemeral streams, desert washes, and water courses with a

subsurface flow. It may also apply to any work undertaken within the flood

plain of a body of water. If you are

planning a project similar to one of the examples listed below, you will need

to notify DFG before you start your project or activity!

|

To formally notify DFG

of a proposed project or activity, you will need to provide the regional

office in your project area with the following:

What happens after

you notify DFG? After the DRG

determines your notification is complete, DFG has a minimum of 30 days to

review your project unless the deadline has been extended by mutual

agreement. During this

time, DFG staff may visit the project site to help them determine whether

your project would harm fish or wildlife resources. If DFG

determines that your proposed project or activity would not cause any harm,

you will be notified that a Lake or Streambed Alteration Agreement is not

required. If, however, DFG

determines that your proposed project or activity could have substantial

adverse effects on fish or wildlife, you will receive a list of steps you

will need to take to protect these resources. DFG staff will work with you to

try to find a mutually acceptable solution. |

|

|

|

|

|

When

constructing, renovating, or adding to a firewise home, consider the

following:

To select a firewise location, observe the following:

In designing and building your firewise structure, remember that the primary goals are fuel and exposure reduction. To this end:

|

Therefore,

consider the following:

Defensible

Space

|

Defensible SpaceHomeowners can greatly reduce the risk of wildfire by creating "defensible space" around structures. Section

4291 of the California Public Resource Code requires clearing flammable

vegetation around structures a minimum of 30 feet, up to 200 feet depending

on conditions. In areas of dense vegetation, at least 100 feet of clearance

is needed. However, on hillsides where fire spreads more rapidly and with

greater intensity, a clearance of 200 feet or more may be advisable. The need to be firewise must be balanced with the need for privacy, shade, and aesthetics. Reducing fuel volume and eliminating highly flammable plants in the defensible space is key to being firewise. Defensible Space

vegetation that is within 10

feet of these woodpiles.

|

|

|

|

|

YOUR FAMILY'S WILDFIRE RESPONSE

PLAN

If

you don't already have one, start now to create a "wildfire response

plan"

for your household.

|

If

you are trapped in a wildfire: You cannot

outrun a fire. Crouch in a pond or river. Cover head and upper body with wet

clothing. If water is not around, look for shelter in a cleared area or among

a bed of rocks. Lie flat and cover body with wet clothing or soil. Breathe

the air close to the ground through a wet cloth to avoid scorching lungs or

inhaling smoke. If Trapped in a |

|

|

|

Who

Is at Risk for Flooding?

Floods are the most common natural disaster

in the U.S., and nearly everybody has some risk of flooding. Virtually every

U.S. state and territory has experienced floods. The Federal Emergency

Management Agency (FEMA) estimates that 10 million U.S. households are

located in high flood risk areas. If you aren't sure whether your house is at

risk from flooding, check with your local floodplain manager, building

official, city engineer, or planning and zoning administrator. They can tell

you whether you are in a flood hazard area. Flood

Insurance You can protect your home and its contents through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) administered by FEMA. Flood insurance is available to owners and occupants of insurable property in communities participating in the NFIP. A flood insurance policy, which you can purchase through your insurance company or agent, is the best way to recover from a flood. Federal disaster assistance, only available if a flood is declared a Federal disaster, is often a loan you have to repay, with interest, in addition to your mortgage loan. In contrast, flood insurance claims are paid even if a disaster is not Federally declared. A flood insurance claim will reimburse you for your covered losses - and never has to be repaid. Contact your insurance company or agent. He or |

she can tell you what your flood risk is and can also provide you with more information about how to obtain Federally backed flood insurance. The Benefits

of Flood Insurance

|

|

||

|

How Should Sandbags Be Used? Sandbags can be used to fill gaps in a

permanent protection system, to raise an existing levee or to build a

complete emergency levee. Sandbags alone, when filled and stacked properly

can hold back floodwater, but they are most effective when used with

polyethylene (plastic) sheeting. Sand is suggested if readily available,

however, it is not mandatory, any local soil may be used. The bags may be

burlap or plastic. Plastic bags can be reused; burlap bags tend to rot after

use. How to Fill Sandbags Fill the bags one-half to two-thirds full.

The bag, when filled, should lie fairly flat. Over-filled bags are firm and

don't nestle into one another; tight bags make for a leaky sandbag wall.

Tying is not necessary . How to Stack Sandbags Stack sandbags so the seams between

bags are staggered. Flip the top of each bag under so the bag is sealed by

its own weight. Stamp each sandbag into place, completing each layer prior to

starting the next layer. Limit placement to three layers unless a building is

used as a backing or sandbags are pyramided.

Short Sandbag Walls For walls four bags high or less, a

simple vertical stack can work. Bolster the wall on the dry side every 5 feet

with a cluster of bags or by providing other support. You may use the

building to support a short vertical stack. Vertical stacks are used to block

doorways also. Caulking weep holes on brick veneer buildings can slow the

passage of water into a building, but water will pass through the brick

itself unless it has been sealed or the building has been wrapped. Blocking

doors and weep holes is not a reliable flood protection method.

Sandbag

Levees Where you need protection from water deeper than 2 feet, the stack of sandbags should look more like a levee. To incorporate 6-mil plastic sheeting into the stack, first lay the sheet along the ground where the outside edge of the sandbag levee will be. It should be 6 mils or heavier, and three times as wide as the intended height of the levee. As you add bags, bring the sheeting up between them in stair-step fashion. |

Tips ►Be

sure you can install the system in the amount of time you have to prepare for

a flood.